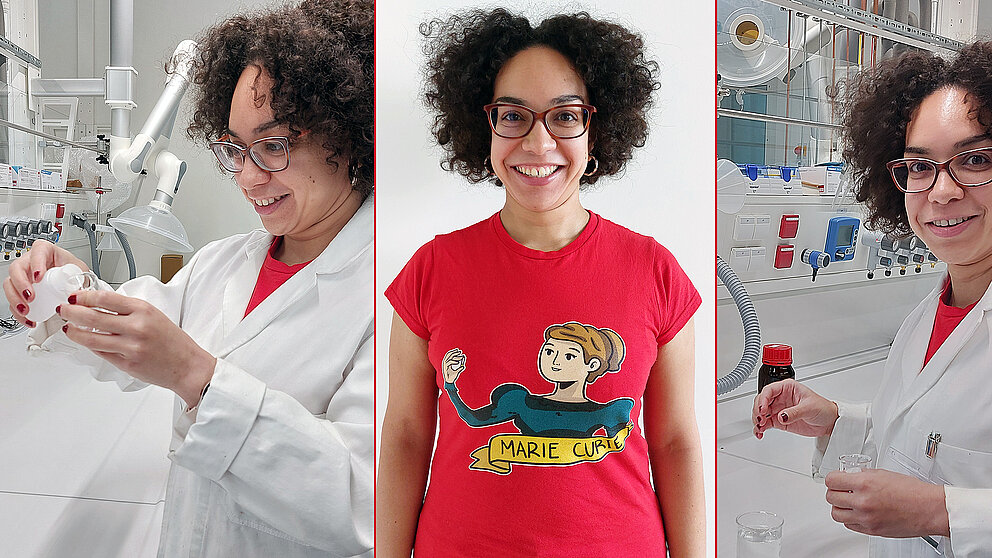

When the Colombian materials scientist and electrochemist Maria Rita Ortega Vega gets down to work in the Faculty of Chemistry and Food Chemistry at TU Dresden, a number of things start to flow: the thoughts in her head on her current research question, the music of the German composer Max Richter that issue from her headphones and the power that she measures in her experiments. “When I sit at my computer to record the results of my lab tests,” she says, “I usually listen to music that suits my mood and the rhythm of my work.”

Apply now!

Maria Rita Ortega Vega came to Germany with a Humboldt Research Fellowship.

Democratic research goal

A Humboldt Fellow since the beginning of 2022, she is a member of Stefan Kaskel’s research group. The chemistry professor recruited her through the Henriette Herz Scouting Programme which brought her to Germany on a Humboldt Research Fellowship. Maria Rita Ortega Vega is developing an electrochemical sensor that is designed to detect kidney disease in humans at an early stage using saliva samples. A research acquaintance, who was already cooperating with Kaskel, drew his attention to Vega. At the time, the postdoc was conducting research and teaching at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre. “I was on the lookout for a postdoc position outside of Brazil. I hadn’t really thought of Germany because of the language.” But a conversation with Kaskel changed her mind. “He was very open and showed his trust in me from the word go. Apart from which, in his team’s work I saw very promising developments with great potential for technology transfer and applications. That sounded really interesting,” says Vega.

Cooperation with my host Stefan Kaskel is very inspiring. I benefit from his experience, have complete freedom in my work and thus develop new ideas for my own research.

She wants to conduct research that has an impact on society. “For me, science is a democratic project. I want to make the materials I work on available to people in concrete applications that make their lives easier.” To construct the sensors Vega uses nanostructured metal ions embedded in an organic network. They react to human urea in saliva and thus point to disease. Her host has been working on these materials for a long time. “Cooperation with Stefan Kaskel is very appreciative and inspiring. I benefit from his experience, have complete freedom in my work and thus develop new ideas for my own research.”

Surprising appreciation

Vega had not experienced this kind of cooperation at home. “In order to drive my research, I left Colombia. Education and science are not a priority of the government there. Going to university is very expensive. Most Colombians can’t afford it. And there aren’t any scholarships.” In Brazil she did find funding and was thus able to start on a career in academia and establish herself. Amongst other things, she drew up a proposal for developing an electrochemical sensor for the early detection of cervical cancer.

In general, she notes, science in Latin America depends to a great extent on the respective government. “In the educational and scientific sectors, the Bolsonaro years were chaotic. Since Lula returned to power there are funding opportunities once again, but hardly any scientists. Some have left the country; some don’t want to work in academia any longer. I, myself, would like to return to Brazil but that depends on the opportunities open to me there.”

Both in Colombia and in Brazil academics were not held in very high esteem: “I was really surprised that that is so different in Germany. Here, you even hear professors talking on the radio as experts,” says Vega. And their status in society seems to be different, too. Just a few weeks after arriving, she joined the choir of Dresden’s Frauenkirche. “When the others heard I was a scientist, they were really enthusiastic and interested in my work. It is not common to receive this kind of feedback in Brazil or Colombia. Our people still don’t understand the role of the scientists in society.”

Become a Scout!

Outstanding professors and group leaders in Germany can directly award Humboldt Research Fellowships via the Henriette Herz Scouting Programme.

Female role models

Another thing that pleases Vega is that the scouting programme that brought her to Germany as a fellow is named after a woman and that the Humboldt Foundation’s family-friendly conditions focus on promoting women researchers. “As a feminist, I think it’s important to support women in research. The situation of women in science is much better today than it was 30 years ago, but there are still many areas – including my subject – that are male dominated. We must keep promoting women and increasing the number of female professors.”

It's crucial to start talking about women in research early on at school. Girls should know right from the start that a career in science is open to them.

A glance at the country report on Colombia, issued by the Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, shows how big the gender-specific differences in research actually are. A study by the Laboratorio de Economía de la Educación, an institution researching into the economics of education at the Pontifical Javeriana University, reveals that the country is making progress, but at a very slow rate. The proportion of women in research grew from 36 percent in 2013 to 38 percent in 2019. In engineering and the natural sciences, the share of female researchers only managed to reach 20 percent.

If you are going to make the scientific world more diverse it is not enough, according to Vega, to appoint a diversity officer. “There should be regular information events in every department – and for everyone.” Moreover, female role models and people who talk about them were required: “My father was a physicist and a great fan of Marie Curie. When I was ten, he told me about her. She was the first woman in the world to become a professor and was awarded two Nobel Prizes – and she was an important inspiration for me on my path into science,” says Vega. She thinks it's crucial to start talking about women in research early on at school. Girls should know right from the start that a career in science is open to them.”

Author: Esther Sambale